A cantilever staircase is one where the solid stone steps (also known as treads) are embedded into a supporting wall on one end, with the other end ‘free’, visible and seemingly floating: the treads are said to be ‘cantilevered’ from the wall.

There are several very good reasons why this form of staircase is so successful and beautiful. One of the key reasons is that the structural principle is simple yet clever, and also elegant yet robust. Another is that they are relatively economic. Let me explain the key principles.

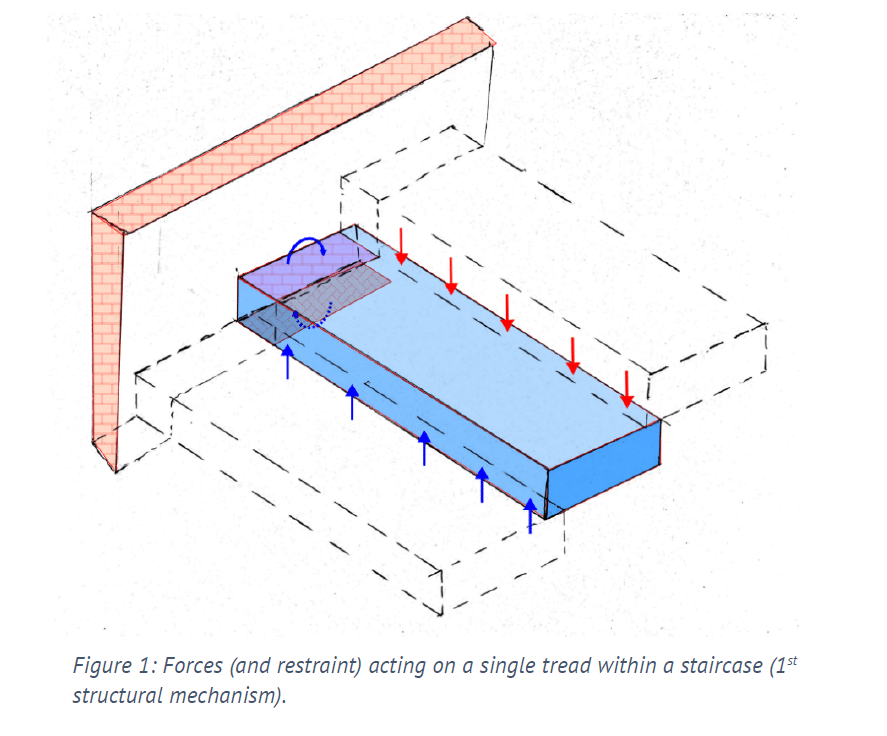

Each tread supports the tread above it, whilst simultaneously using the tread below for its own support. If you imagine the tread attempting to transmit this load (weight) from the tread above it to that below it without being embedded into a wall, it would simply tilt or ‘twist’ and fall down. It only takes a relatively small amount of twisting restraint from the wall embedment to enable it to carry (i.e. transfer) the load. Each tread has to be clamped by the wall. In reality therefore, each tread is not acting as a pure ‘cantilever’ projecting from the wall, although it is reliant on the wall for its twisting restraint. This is a subtle but important difference, both for the tread itself and in terms of the demand placed upon the supporting wall.

The diagram (Figure 1) attempts to depict the forces (loads) and restraint (wall clamping action) on a typical tread in a staircase.

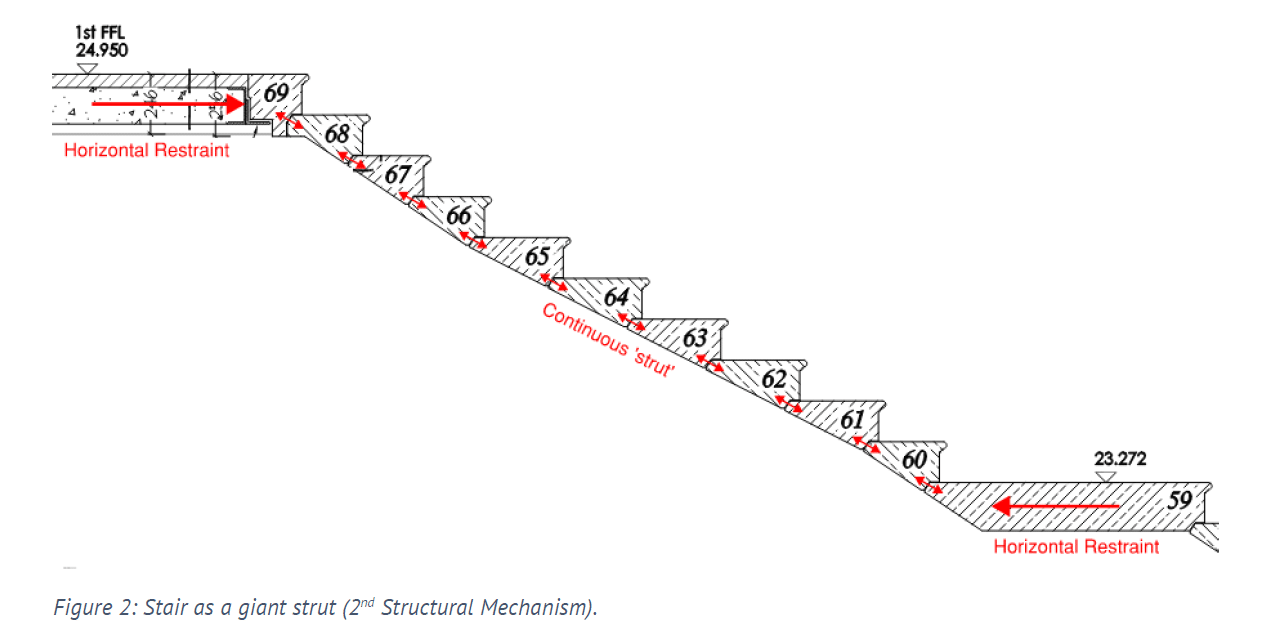

For most modern cantilever staircases, instead of just treads sitting one onto the next, they also have an overlap or interlock detail at the ‘throat’ of the stair (the thinnest part). This detail enables the treads to press onto the one below on an inclined line of force, which forms a kind of giant inclined ‘strut’ (albeit that the force progressively increases as the weight builds up towards the bottom of the stair). This action can only take place if there is adequate ‘horizontal restraint’ at both bottom and top of the run of steps – which is normally easily provided naturally by floors and landings. This mechanism creates additional assistance to the stair to that described earlier. And most importantly, without going into too much detail, the horizontal restraint forces actually REDUCE the torsions (i.e the twisting action) experienced by each tread (from the first mechanism shown in Figure 1 above).

It is worth mentioning that a chain of struts like that shown in Figure 2 would normally be hopelessly slender and ’buckle’ (i.e. fail sideways). However, the wall restraint to each tread (as in Figure 1) keeps each position in the chain of struts stable (i.e. restrained from movement or twisting), and therefore enables the whole stair to act as one and remain strong and stable. Miraculous!

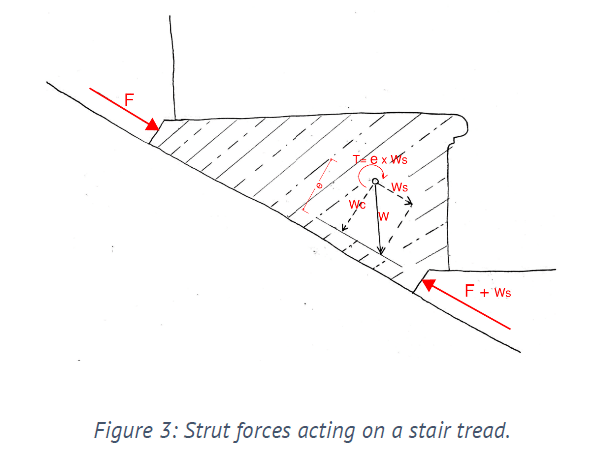

At a micro level, the strut forces both assist the tread support and also cause local torsions too (see Figure 3). The shape of the treads (shape in cross section) effects the ‘centroid’ location and also the ‘stress’ (density of force or twist in the material) within each tread. This is far too complex to try to explain here – but it illustrates, to an extent, why a specialist stone structural engineer must check over each design and verify the stresses are lower than the capacity of the selected stone.

At a micro level, the strut forces both assist the tread support and also cause local torsions too (see Figure 3). The shape of the treads (shape in cross section) effects the ‘centroid’ location and also the ‘stress’ (density of force or twist in the material) within each tread. This is far too complex to try to explain here – but it illustrates, to an extent, why a specialist stone structural engineer must check over each design and verify the stresses are lower than the capacity of the selected stone.

So this all sounds like a lot of complexity and interdependency? Kind of; but notice that each tread could work independently as a cantilever if it needed to as well (we haven’t even talked about that mechanism earlier!);

And the interlock with the nearby wall provides further, multiple opportunities for horizontal restraint planes – which means that the stair may not necessarily be fully dependent upon the discrete floors and landings for strut restraint (so this is another mechanism not described earlier either).

Furthermore, a loss of torsional capacity in one tread alone would not be catastrophic for the stair (again a bit complicated to explain here but basically the torsion in the failed tread would or could be shared back to the adjacent treads – assuming they are intact of course). Resilience!

So, all in all, the combined system of a cantilever stone staircase has so many ways to ‘stand up’ that is gives resilience, safety, and ultimately longevity. This structural resilience must partly account for why so many of these stairs have stood the test of time and are also suitable for today’s stringent structural criteria and the design codes.

Spiral & Curved stairs

Spiral & Curved stairs

The tighter the internal curve of the ‘free’ edge of each tread, the more ‘vertical’ the inner strut becomes. With a near vertical support strut line at the inner edge means that each tread experiences very little twisting (torsion) and so are extremely strong and stable, needing very little assistance from the outer wall restraint.

The inner line of the stair looks extraordinarily fine, flowing and elegant and is just a joy to experience.

Slenderness

Due to all these efficient structural mechanisms at play, the ‘throat’ of the stair, seen at the free edge, can be very narrow indeed. And by keeping it quite small the self-weight of the stair is also reduced anyway – bonus.

Compare this to concrete where structural engineers will want at least 100mm and two sets of reinforcement. Consider the difficulty of casting concrete to such a shape & slope. And then factor the cost of cladding this concrete with something beautiful …. like stone!

All other forms of staircase have bulk and clumsiness compared with efficient and slender solid stone cantilever staircases. Another big reason for their popularity.

Value

Because of the inherent slenderness and natural beauty of stone, there is generally no need for any other finishes or materials (e.g. to the soffit, or to the side stringer line). So the stone itself is the structure and the finished product once installed. This means that, whilst they would not be classified as a ‘cheap’ option by any means, when assessed against all the ancillary costs of other forms, such as a clad concrete structure, they are very likely to represent very good value indeed.

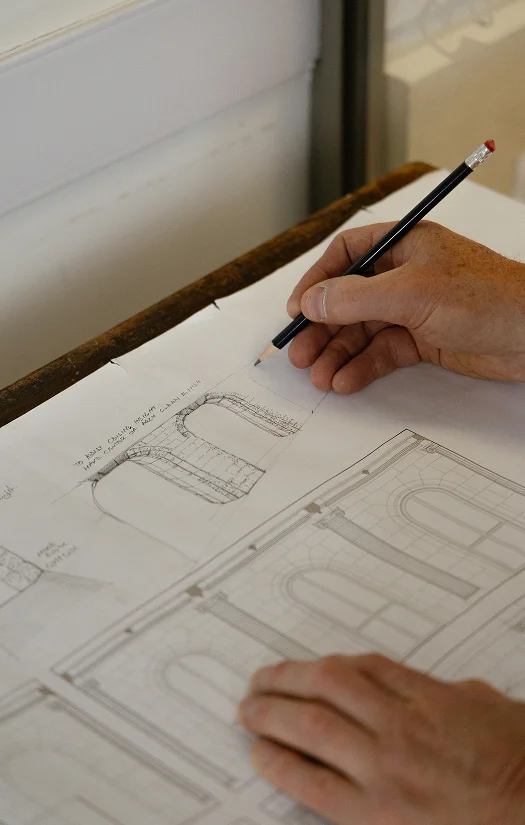

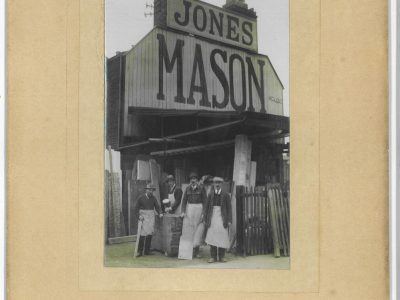

At A F Jones, we have designed, made and installed literally hundreds of cantilever staircases using a variety of different stones. We have not heard a single client regret investing in one.

Ken Jones

February 2021